$1,000

GOODBYE, MOTHER

Oil on Canvas, 30” x 40",” 2024.

-

Goodbye, Mother is one of only a few paintings in my current collection that started without an idea. That is to say, I painted it before I knew what it was. I was in a funny place aesthetically when conceptualizing this new piece. I was hyper-fixated on space age design, the Riot grrrl movement, Rococo, and maintaining a practice of Hellenic Paganism. It’s amusing to me now to see all of these odd little monomanias peeking out at me from the canvas. Not quite as amusing though, as my attempt to have a religious practice.

-

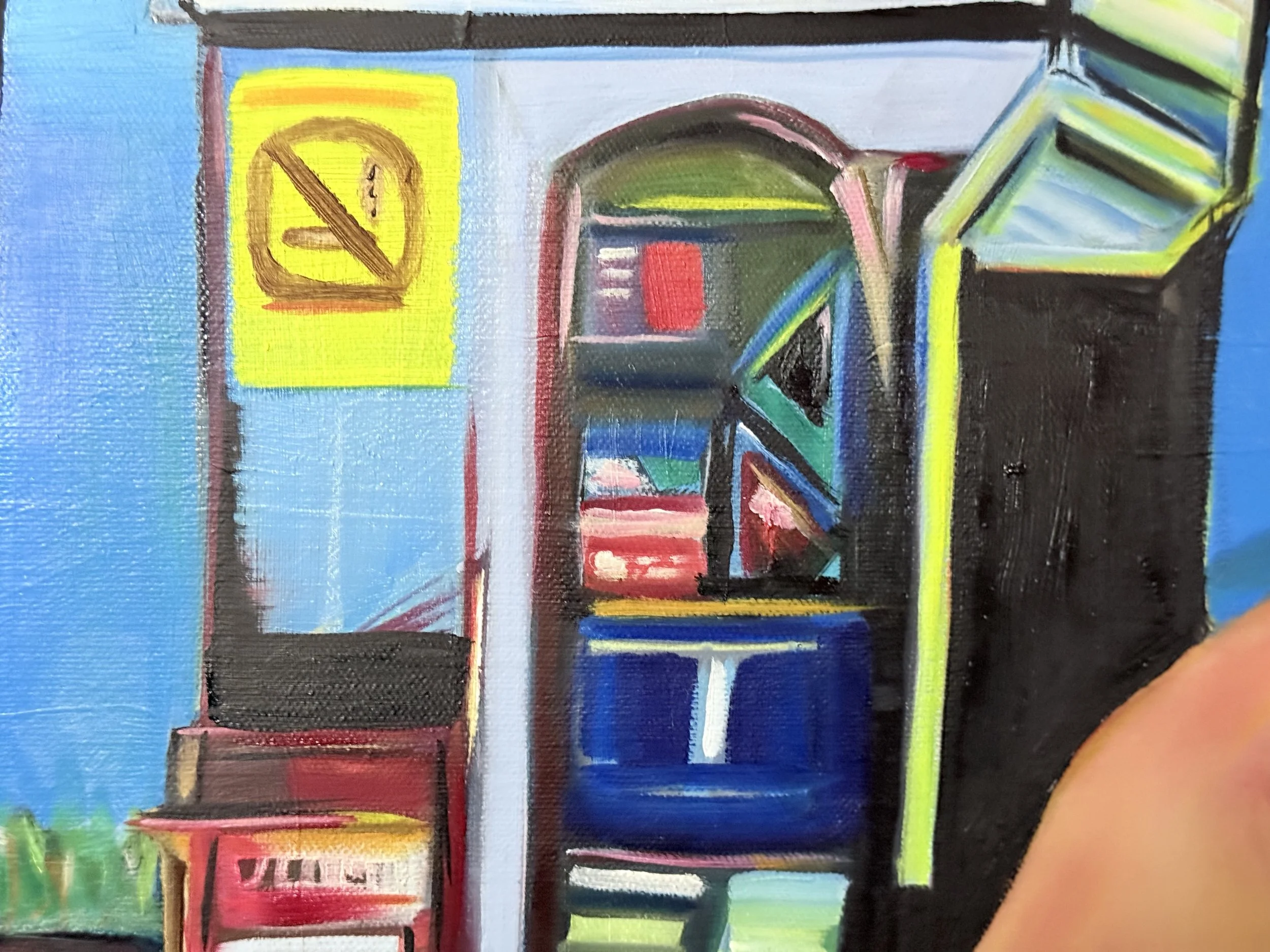

The intention of this piece took shape in the painting of it. Each stroke was guiding me across, and, suddenly it started asking questions of me. The significance of each physical element contributed to delivering the message. One question lingered longest: When did we stop caring? The hint is on full display at every gas station worldwide.

-

The lens through which this painting emits meaning is allegory. It draws a parallel between mythical gods and our modern ones. The link between our world as humans and the world of deities is myth. We have created these myths since our origin in order to leave the answers to the gods who, thankfully, do not speak.

-

We still create our own myths. Look to the myriad green-washing companies who announce new sustainable, eco-friendly, low-emissions products in a commercial dripping with pathos. Notice how when a likable celebrity starts pushing a product because its “planet friendly,” no one mentions that the label is just green now and that it is still, in fact, snail mucin. Its myth! We believe it when it behooves us, which is typically when it paints us as heroes.

-

This allegorical portrait features the goddess, Demeter. She is the embodiment of humankind. I say humankind and not humanity to infer that it is our nature as humans that is being referenced here. Humanity alludes more to our identity as human beings and not the experience of being human. It is in our nature, thus, that we would/should care for our place of existing—if not for the health of our habitat itself, then at least, in the interest of self-preservation.

-

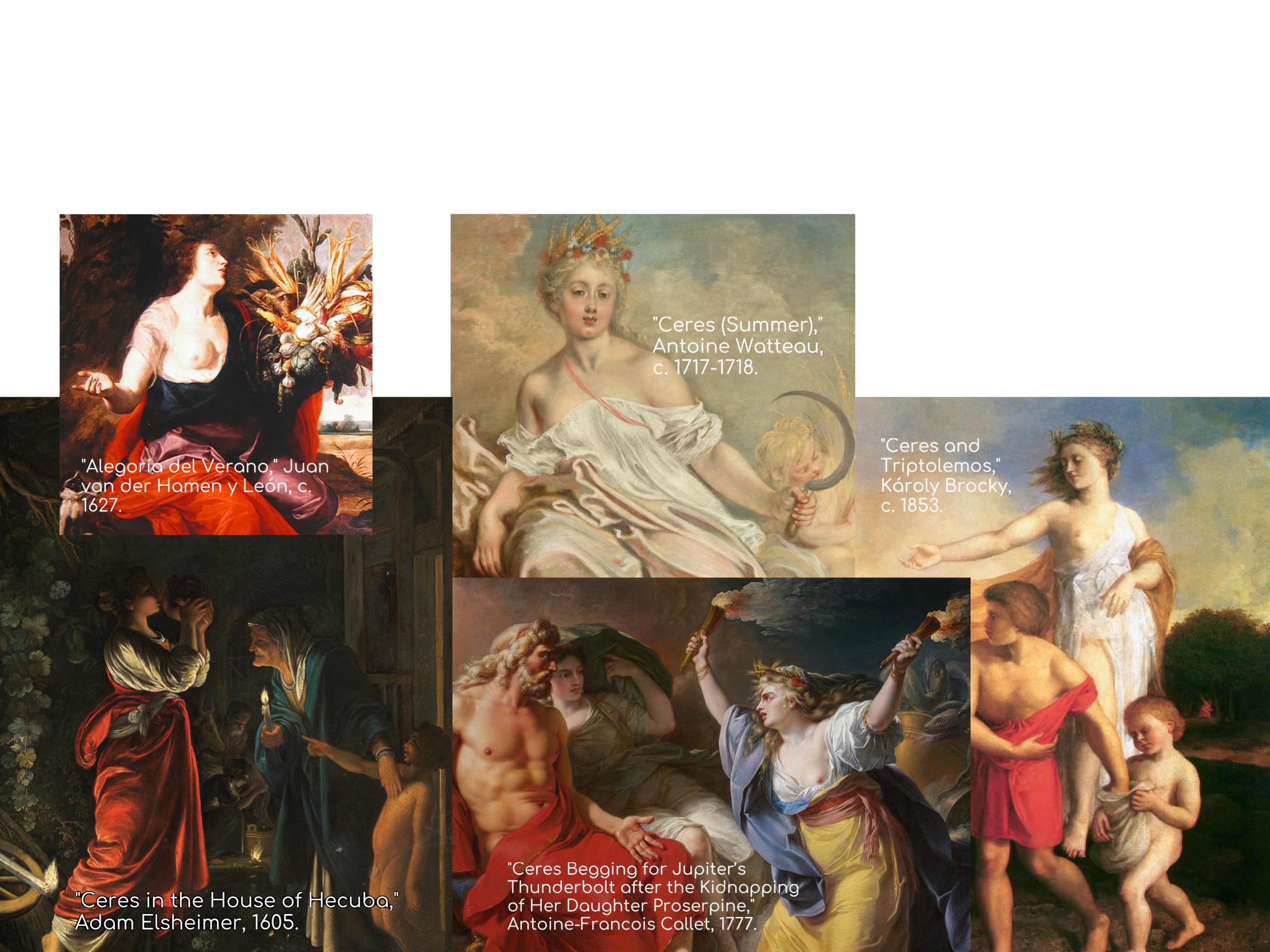

Demeter is the goddess associated with agriculture, harvesting, and the overall care of the earth. One of her epithets is ‘the corn-goddess.’ Additionally, she is praised as the goddess of fertility and motherhood. Representations of Demeter, (Roman name, Ceres), are ubiquitous in fine art. For centuries, her portrayals have evoked a sense of safety due to her dominant characterization as a mother to the earth. Even when she is poised in authority and ire, it feels like we are the ones she is protecting. We can see some of ourselves in her. But we ought to see the darker truths inside the myth. Mother may not always be here.

-

Painters across all disciplines and movements immortalized her as a gentle matronly farmer, attentively tending to crops; a road-weary mother, searching for Persephone; and, perhaps the rarest characterization of the goddess: as a militant queen. A preponderance of portrait studies have presented Demeter as a buxom harbinger of doom, flailing in throws of hysteria. The pervasiveness of bare breasts in this ilk of illustration should not go unnoticed.

-

Here, in the world of this painting, Demeter’s breasts are painted without nipples, giving her an anthropomorphic quality that confronts our expectations of physical femininity. This, is in addition to inevitable sexual tension, which, for me, is a neutral perspective that only holds merit when sex is useful to the story. In this case, it is not. Once the anatomical incongruity is clear to the viewer, they can see past the nudity and witness a woman ‘without.’ Persephone descends, taking with her Demeter’s need, desire, and ability to be a Mother. Her departure in Greek mythology initiates the barrenness of winter.

-

As her daughter drives away in the painting—a blur escaping the canvas—Demeter lights a cigarette. In the lore of this artwork, this initiates the allegory of Demeter’s carelessness as the harvester’s neglect, the nurturer’s abuse, and our own existential apathy. Hellenistic Greeks saw the cold wrath of winter as the agricultural and environmental display of Demeter’s rage. Here, however, it is ambivalence and disregard that preempt destruction. A parallel emerges between myth and reality, and we hesitate to ask the question because we already know the answer.

Are we Demeter?

-

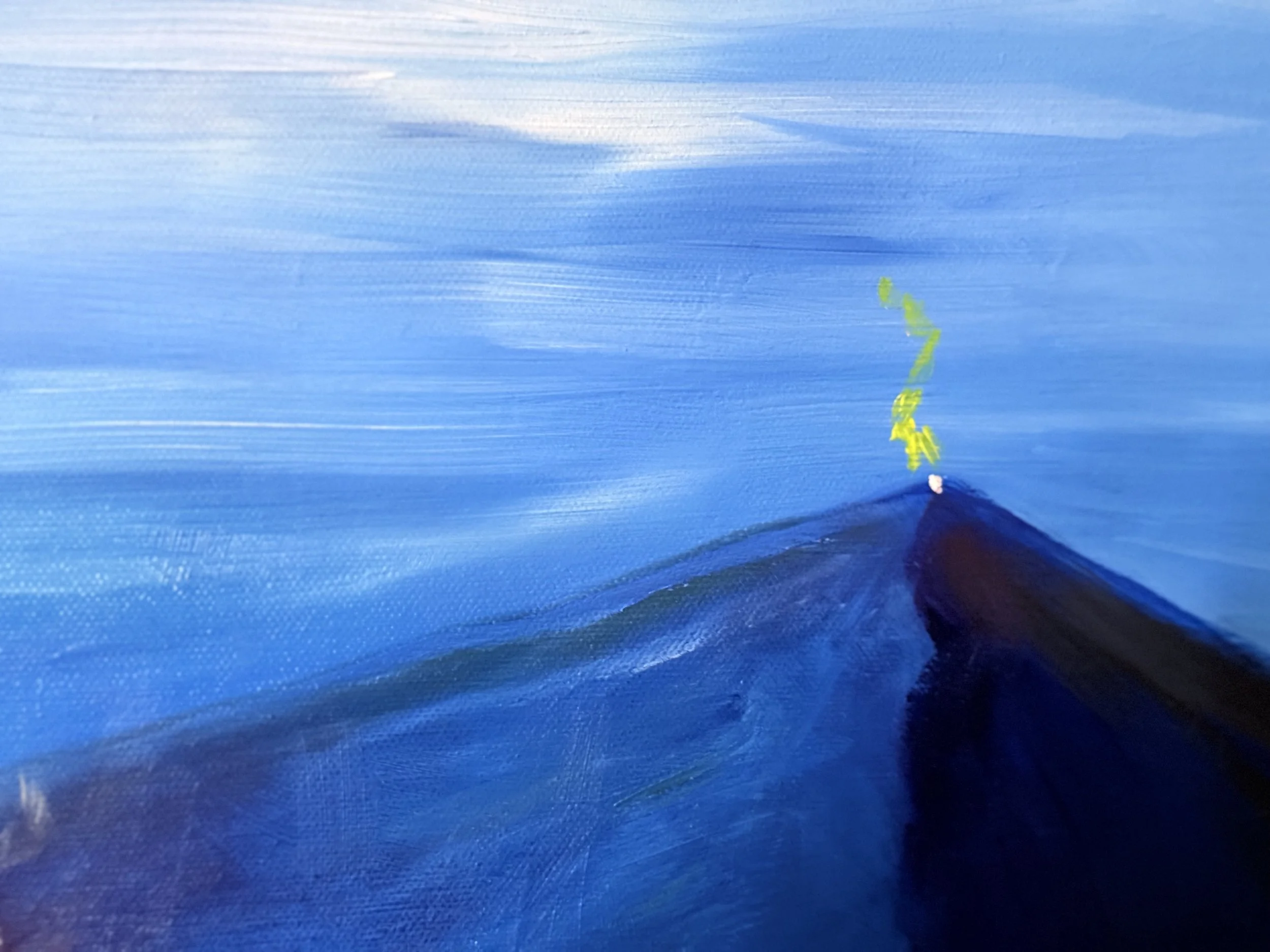

Someone watches from atop the Herculean mountain in the distance. The whisper of a lightning bolt is tethered to the apex. The exaggerated scale of the mountain alludes to the insurmountable disdain of mythical gods, which are merely deifications of earthly oppressors. Their modern counterparts are undoubtedly the corporate industrial machine and his girlfriend, technology. They light fires with one hand and in the other sell us the hose. Is this not an indication of art becoming life, or rather, myth becoming reality? We sacrifice necessity for nobility while the demigods at Soho House buy more storage for the harvests they receive for free.

-

She sits in unfettered defiance of the danger she is igniting. Her back is turned to reason. Her body feels clenched at sharp sweaty angles in late September’s heat. The cornfield’s stalks shed their green sheaths as golden decay rises toward the sun.

-

Ancient Greeks bore no resentment for Demeter’s neglect. They continued to honor and worship her for centuries and, to my knowledge, she has yet to be cancelled by modern mortals. After all, she was a goddess and certainly one of the most benevolent in a group of narcissistic psychopaths. Do we forgive ourselves our trespasses like we do our gods? Do we allow ourselves permission to turn our backs to the looming chaos because we, perhaps, deify ourselves?

Are we Demeter? No. The consequences of our neglect will have no recourse or recompense. Our epic won’t get the grace of revision, nor will our carelessness be improved upon by a better ending.

-

-